Human Rights and the Age of Inequality by Samuel Moyn (Themes, Summary, Analysis and Interpretation)- NEB Grade 12- English

About Author

Samuel Moyn is Jeremiah Smith, Jr. Professor of Law and Professor of History at Harvard University. In 2010, he published The Last Utopia: Human Rights in History and his most recent book is Christian Human Rights. His areas of interest in legal scholarship include international law, human rights, the law of war, and legal thought, in both historical and current perspectives. In intellectual history, he has worked on a diverse range of subjects, especially twentieth-century European moral and political theory. He has written several books in his fields of European intellectual history and human rights history. His book Not Enough: Human Rights in an Unequal World (2018) is the most recent work. He is currently working on a new book on the origins and significance of the humane war for Farrar, Straus, and Giroux. Over the years he has written in venues such as Boston Review, the Chronicle of Higher Education, Dissent, The Nation, The New Republic, the New York Times, and The Wall Street Journal.

Before you go to the essay, please know about Croesus:

Croesus was the magnificently wealthy ruler of the Lydian Kingdom during the middle of the sixth century B.C. His extravagant riches made him famous, but even he could not escape hubris, destroying his own kingdom and forcibly joining the ambitious Persian Empire around 547 B.C.

The Essay

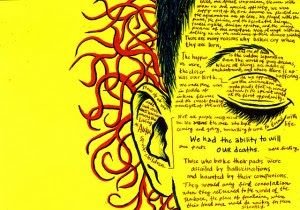

In “Human Rights and the Age of Inequality,” Samuel Moyn deals with the drastic mismatch between the egalitarian crisis and the human rights remedy that demands not a substitute but a supplement. He points out that the human rights regime and movement are simply not equipped to challenge global inequalities.

In comparison to the world in which we live today, where few enjoy these benefits, Croesus offers a kind of utopia. It is the utopia foreseen in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948)1, whose goal is to provide a list of the most basic entitlements that humans deserve thanks to being human itself.

We increasingly live in Croesus’s world. It now goes without saying that any enlightened regime respects basic civil liberties, though the struggle to provide them is compelling and unending.

The founding document of human rights announced status equality: according to its first article, all human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. It may be true that, in a world devastated by the evils of racism and genocide, the assertion of bare status equality was itself a revolutionary act.

Human rights, even perfectly realized human rights, are compatible with inequality, even radical inequality. Staggeringly, we could live in a situation of absolute hierarchy like Croesus’s world, with human rights norms as they have been canonically

The ‘West’ for a long moment agreed about the importance of socio-economic rights. Indeed, it was in part out of their own experience of socio-economic misery, and not only the threatening communist insistence on an absolute ceiling on inequality, that the capitalist nations signed on so enthusiastically to welfarism.

Indeed, it is perhaps because human rights offered a modest first step rather than a grand final hope that they were broadly ignored or rejected in the 1940s as the ultimate formulation of the good life.

Franklin Roosevelt issued his famous call for a “second Bill of Rights” that included socio-economic protections in his State of the Union address the year before his death, but the most important three facts about that call have been almost entirely missed.

The most interesting truth about human rights in the 1940s, indeed, is not that they were an optional and normally ignored synonym for consensus welfarism but that they still portended a fully national project of reconstruction – just like all other reigning versions of welfarism.

The harmony of ideals between the campaign against abjection and the demand for equality succeeded only nationally, and in most North Atlantic states, and then only partially.

Even the decolonization of the world hardly changed this relationship, since the new states themselves adopted the national welfarist resolve.

Another human rights movement?

Could a different form of human rights than the regimes and movements spawned so far correct this mistake? the writer doubts it.

Yet if the human rights movement at its most inspiring has stigmatized such repression and violence, it has never offered a functional replacement for the sense of fear that led to both protection and redistribution for those who were left alive by twentieth-century horror.

Human rights movements face a deeply strategic choice about whether to try to reinvent themselves – or whether to stand aside on the assumption that as inequality grows, someday its opponent will arise.

Comments

Post a Comment